by Stephanie Larson

For my semester-long project, I intend to create a game that answers the following question: How does literacy as a thing with material, durable, and active attributes get sponsored across local and global contexts? I seek to strengthen an understanding of how Deb Brandt and Katie Clinton grasp and deploy literacy’s “thing status” in transcontextualized terms (2002). Thus, I am grafting Bogost’s concept of procedural rhetoric onto Brandt’s work of literacy sponsorship (Bogost 2007; Brandt 2001). This game will expose not only how the detailed processes that simulate sponsorship are convincingly rhetorical, but more simply, this game will reveal how the materiality of literacy sponsorship works. Procedural rhetoric proves productive for this question because procedurality, as Bogost defines and uses it, strives to understand how video games propose processes of persuasion that are embedded into the complexity of games. In other words, procedures provide a way to tease apart the interworking of an ambiguous system. Procedurality can tackle operational systems in detailed ways, and this game will unveil relationships between sponsors—human and non-human—that maintain, negotiate, sanction, or reject literacy’s connection across local and global levels.

Before conceptualizing the game itself, I need to account for how sponsors function microscopically within larger economic and political structures. The goal for my alien phenomenology project attempts an ontography of my own literacy sponsorship as a way of dissecting how I will use sponsors in the final project. Here, I will provide a brief explanation of literacy sponsorship as identified by Deb Brandt in her book, Literacy in American Lives (2001). Brandt responds to a lacuna in literacy research up to 2001 that she believes neglects an understanding of literacy as material that confers value. She treats literacy as a resource with economic, intellectual, political, spiritual, and global power. In doing so, Brandt crystallizes “what has made controlling literacy so alluring to the powerful” (Brandt and Clinton, 355). By viewing literacy as a commodity with private and public value, Brandt establishes why literacy has the power to reward and simultaneously exploit. Sponsors have the ability to grant or reject access to literacy, which holds lucrative value in our society. Brandt underscores the material and transferable qualities of literacy pointing to sponsors as a “tangible reminder that literacy learning throughout history has always required permission, sanction, assistance, coercion, or, at minimum, contact with existing trade routes” (Brandt 19). Brandt understands that because of the swift and fluctuating economic conditions, altering sponsors constantly exacerbate the process of obtaining literacy. Sponsors, then, can be global or institutional forces, such as economic or corporate systems, or sponsors can be local or communal forces, such as family members or writing utensils.

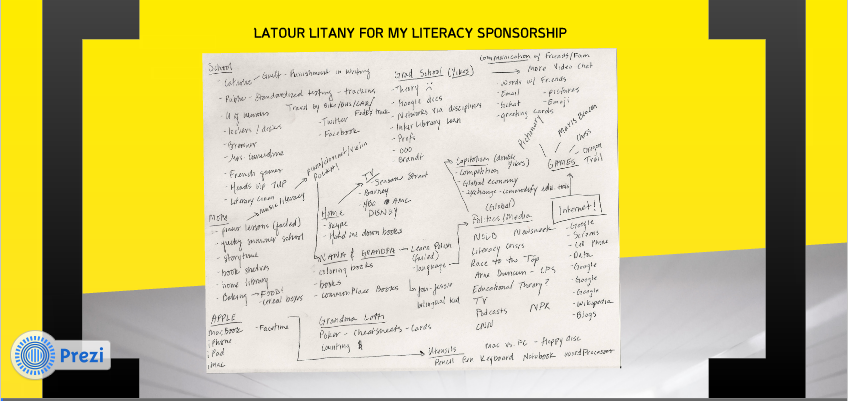

I began this project with what Bogost defines as a “Latour litany,” cataloguing potential sponsors throughout my history that have bolstered access to literacy (2012). While furiously recording my sponsors, I realized I was contradicting a main pillar to the method of list-making: “incompatibility” (Bogost 40). While my list was messy, I found myself making connections between sponsors through my own human subjectivity. I wanted to rupture this sentimentalizing of sponsors, which was occurring because of my connectivity. I returned to Alien Phenomenology and began embracing ontography beyond lists. Bogost states, “The Latour litany gathers disparate things together like a strong gravitational field. But the Shore ontograph takes things already gathered and explodes them into their tiny, separate, but contiguous universes” (Bogost 49). To explode my universe, I turned to Prezi.

Prezi provided me the opportunity to expand my litany in a more ontographical display. I wrestled with amalgamating my sponsors under one umbrella without the subset categories of home, school, etc. But for the purposes of introducing my project of literacy sponsorship to the class, I wanted to somewhat organize my sponsors to show how I’m thinking of them under various societal categories. The important thing to note is that in this ontography, large corporations, such as Disney, are considered equal to a tool, such as a bendable pencil, in the grand scheme of sponsorship. Bogost points out that “[t]o create an ontograph involves cataloguing things, but also drawing attention to the couplings of and chasms between them” (Bogost 50). My ontograph is appropriate because it equally represents how these “things” participate and/or compete to influence literacy. This ontograph registers my literacy sponsorship showing the density between humans in equal relation to their non-human counterparts. In addition, Prezi’s ability to zoom in and out forces the viewer to absorb the ontograph whole at once, while diving into the infinity of material. For example, the Wiki excerpt of John Dewey may cause one to address sponsorship according to Dewey’s pragmatic and progressive educational philosophy. On the other hand, one may note Wikipedia’s staple display of representing biographical information as the example of sponsorship. I found myself making these layered interpretations that differed from my original intention of choosing the object. This shows how my ontograph forces the viewer into the messiness that the pictures, videos, symbols and words offer. Like Shore’s photography, one must unpack the layers of literacy sponsorship within each artifact.

After creating the ontograph, I realized I had not left procedural rhetoric for the game itself; rather, procedurality is at play within this ontograph. I argue through watching the Prezi based on the processes I’ve ordered, I’m persuading the viewer to capture literacy in an overwhelmingly material, digital, multimodal way that fosters a multitude of interpretations. The process of travelling from frame to frame, absorbing different sponsors presents a new way to account for interobjectivity by flattening all sponsors and then loosely linking them without any anthropocentric narrative. One might guess the significance of a sponsor, but the interpretations are limitless. The beauty of this ontograph is that it forces me, the game creator, to look at my own sponsorship in different ways to see the multiple layers at work. In this medium, literacy travels in digital, nonhuman form across local and global levels while accounting for the physical world as well.

Works Cited

Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology, Or, What It's like to Be a Thing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2012. Print.

Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2007. Print.

Brandt, Deborah, and Katie Clinton. "Limits of the Local: Expanding Perspectives on Literacy as a Social Practice." Journal of Literacy Research 34.3 (2002): 337-56. Print.

Brandt, Deborah. Literacy in American Lives. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001. Print.

Videos used in Prezi:

“Jane McGonigal: Gaming Can Make a Better World”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dE1DuBesGYM

“Apple iPhone 5-TV Ad-Orchestra”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UWOF0bBec2Q

“RSA Animate: Changing Education Paradigms”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U

“Duncan: No Child Left Behind ‘Broken’”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jb1H55wUm50

“Sesame Street: Patti Labelle Sings The Alphabet”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G0hYxuDav0g

“Tucker Piano Dec 7’2010.wmv”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PiblYasnzWE